Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

What Is Civil Technology?

The Technological Process

A Brief History Of The Built Environment

An Introduction To The National Building Regulations

What Is Civil Technology?

Civil Technology focuses on concepts and principles in the Built Environment, as well as on the technological process. It embraces practical skills and the application of scientific principles. This subject creates and improves the Built Environment in a way that enhances the quality of life of the individual and society and ensures sustainable use of the natural environment.

Professions related to the Built Environment, such as architecture, engineering, project management, property valuations, landscape architecture and quantity surveying, are the basis on which civilization was founded.

It is through these professions that essential services, such as roads, bridges, purified water, water-borne sewage, railway lines, high rise buildings, factories and residential housing in general, among its many aspects, are provided. The subject Civil Technology aims to create an awareness of these aspects in learners and society.

We however find the term Civil technology to be misleading when trying to explain to somebody about the building process and have hence called this guide the “How to of Building”.

The Technological Process

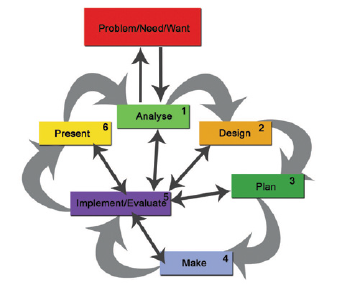

In any aspect of life, problems need to be solved, decisions made and action taken. The technological process is just the same. Throughout the greater process, there are many smaller processes that must take place:

- Analyse the problem, need or want

- Design and develop alternative solutions

- Plan the chosen solution

- Make or manufacture an example of the chosen solution

- Evaluate the example

- Present the information and example

As you can see from figure 1.1 – every step of the process needs to be evaluated and then implemented. Also, each stage of the process has its own more detailed process. For example, designing can involve a number of steps before the design is satisfactory. That would mean evaluating the design throughout the process, analysing the problems encountered, and implementing changes.

In everyday life, a process takes place all the time. Even something as simple as deciding what to wear for the day is a result of a process. Obviously, a decision like that does not require a manufacturing process, but it does require a thought process.

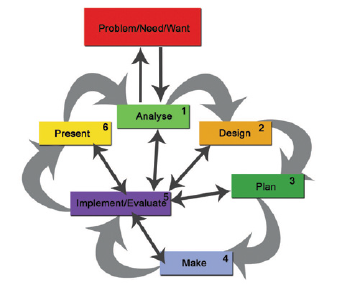

The problem/need/want to become a building professional

Analysis

- What are the various options within the building industry?

- What do I need to study at school?

- What marks do I need?

- Where can I study further to achieve my goal?

- What is the cost of further studying?

- What can I earn in the chosen field?

- How long is the course?

Plan/Make

- Apply to a further education institution or university

- Work hard to achieve the required results

- Spend time with a qualified person in your chosen field to get some experience and a better idea of the practical aspects of the job/career (mentorship)

Implement/Evaluate

- Make an application to study further

- Am I able to achieve the marks required?

- Do I like the working environment I will be in?

- Can I afford to study further?

- Am I happy with the lifestyle I can achieve with the profession I have chosen?

Present

Finalise the decision. Once all the evaluating and planning and working have been completed (e.g. you have achieved your matric with a university entrance and you have been accepted to a further education institution to study your chosen profession), the final decision can be made about what you want to do.

This is a very simple example of what happens on a daily basis. While we may not be aware that we are thinking in terms of this process all the time, and certainly we do not consciously go through the process step by step, it happens anyway.

The technological process is a natural process that we are all capable of doing.

A Brief History Of The Built Environment

The Built Environment is a very formal term for what is essentially an everyday progression of society’s needs. The phrase Built Environment refers to the man-made surroundings that provide the setting for human activity. The very basics of civilised man’s needs are addressed within the context of the built environment, such as shelter, water, electricity, transport, sanitation (cleanliness) and safety. A lot has been written about the engineering and architectural feats of ancient civilisations such as the Egyptians and the Romans. Today, structures still standing are a testament to the sheer brilliance of these ancient people.

Historically, man has created ways in which to accomplish all of the above in any way possible. When engineering was not available for making roads, people and animals simply took the path of least resistance, creating a well- used pathway for others to follow. Man would generally settle or at least spend some time near water. There was no need for services such as rubbish collection because no rubbish existed.

Whatever materials were available in the immediate environment were used to build homes. Mud, stones, tree branches, grass, etc. were all used in the most ingenious ways to create easy to build, stable shelters that addressed the lifestyle of the people building them. For example, American Indians used animal skins and tree branches to build teepee’s (tents). These were not permanent structures because they were transient people who had to move with their food source (buffalo).

The Bushmen or San, were similar in that they travelled with the herds of animals they hunted for food. Their homes were made from small trees and branches and woven in a complicated pattern to create what looked like an upside down basket. These homes were brilliant because in the rain, the wood swelled and kept the rain out, but in dry weather, the small gaps between the branches allowed cooling air to flow through.

When man became more pastoral (settling down to farm animals and grow crops), structures became more permanent. The Khoikhoi built huts very similar to the Bushmen, but these were permanent structures. The Nguni used sticks and grass to create their huts, which were constructed of a framework of semi-circular arches, crossed with another set of arches. These were built up in height towards the middle to produce a dome. The structure would then be dressed with plaited grass ropes. The floors of these huts were made using cow dung, clay and ox blood.

Later, the migration of Pedi, Tswana and Venda people brought about the creation of rondavels. These were made of mud walls with thatch roofs. The creation of these buildings made a statement about the change in lifestyle of these people from nomads to settled farmers.

From a security point of view, shelters were often built in a circular fashion, surrounding an inner space where animals were kept in order to keep them secure. Also, Kraals were created using branches from thorn trees to create a fence around the perimeter of the building circle to keep out wild animals.

The stone- and iron-ages brought with them innovation in the way man hunted and lived. Better and stronger tools allowed man to be more creative in the materials used for building structures.

Architecturally, traditional homes were built for practicality. The only artistic elements were generally for spiritual reasons. There were no conveniences and life was not easy, therefore decoration had to have a specific purpose and reason. Modern architecture and building, which still uses the same basic materials (stone, sand, wood) should address practical issues as well as artistic elements. With technology advancing

as fast as it is, more and more new building components are introduced to the building industry – from plastic window frames to see-through concrete.

However, any type of building material or building method has to comply with certain rules, set out in the National Building Regulations SANS 10400 (see next sub-section). When man learned to cultivate land for crops and to breed animals, populations began to grow and with more and more people settled in one place for long periods of time, other needs were identified and cultures changed in order to adapt.

For example, one of the first permanent buildings built in Johannesburg was a hospital (which was more often than not used as a jail). With more people populating an area, the need for services grows. This is where the professions within the Built Environment stemmed from.

A lot of what we take for granted today is a result of the organisation of the built environment. Today we can turn on a tap to get water instead of having to walk kilometres to collect water from a river. We can also flush a toilet, switch on a light, cook on a stove and watch the world on TV.

An Introduction To The National Building Regulations – Sans 10400

Development in the building industry is a continuous process. With the passage of time, new materials become available, design methods are refined, and innovative building systems are introduced. Political change also results in the development of new policies and approaches to various aspects of building and construction that might impact on regulatory requirements. It is therefore obvious that building regulations and the interpretation thereof cannot remain static if they are to accommodate such policy changes and allow for the early use of innovation in construction; and are therefore updated on a regular basis.

The National Building Regulations do not purport, and were never intended, to be a handbook on good building practice. They set out, in the simplest and shortest way possible, requirements to ensure that buildings will be designed and built in such a way that persons can live and work in a healthy and safe environment.

The How to of Building – will assist in the interpretation of these standards and adds a practical approach to the implementation of the National building regulations. There are other aspects of a building that might affect only the comfort or convenience of people, but these are not controlled by the National Building Regulations. Market and economic considerations will obviously also limit the degree to which these matters can be considered in the design of a building. It is important, therefore, that entrepreneurs, designers and building owners should be aware that the mere fact that a building complies with the National Building Regulations does not necessarily indicate that it is a desirable building.

There are many aspects to be considered and the relative economic worth of each should be related to the final cost of the building. Professional designers are trained to take these matters into account and can be expected to do so without any obstructive and possibly inhibiting and inappropriate control by the Regulations. In the case where the designer of a building is not professionally qualified, there is a wealth of information on good building practice available in books like the How to of Building and from organizations such as the CSIR, the South African Bureau of Standards, the National Home Builders Registration Council, the South African Institution of Civil Engineering and various trade associations.

In order to understand and interpret the National Building Regulations correctly, it is important to understand the philosophy and intent behind the Regulations. One aim of the drafters of the Regulations was to keep the number of Regulations to a minimum. It was therefore decided that, as far as possible, the Regulations should be concerned only with the health and safety of persons in a building, that all technical aspects should be covered by functional regulations and that the Regulations should be written in such a way that they assist rather than impede the use of innovative building systems and designs. This philosophy was taken a step further in the current amendment of the interpretation of the regulations by introducing the concept of two different types of buildings to cater for different user needs and expectations.

A new category of buildings (category 1 buildings) has been introduced in certain classes of buildings that have a floor area not exceeding 80 m² to make buildings affordable to poorer communities. The revised SANS 10400 allows choices to be made in the performance requirements of certain attributes for buildings falling within this category. Such buildings have comparable safety standards with buildings not so categorized, but may, depending upon the choices exercised in respect of particular attributes, have different resistances to rain penetration, deflection limits, maintenance requirements, lower levels of natural lighting, etc. It should, however, be stressed that choices exercised in respect of these buildings relate only to the performance of some of the attributes of such buildings. The nature of developments is determined by environmental and town planning processes which are independent of such choices. This should be kept in mind by any local authority when assessing a building in terms of these revised functional regulations.

In applying the National Building Regulations it will be found that, in certain instances, there is an overlap with the requirements of regulations made in terms of other Acts. Some of these anomalies have been overcome by suitable amendments to other regulations, but there are some regulations made in terms of local town planning schemes that it might be desirable to retain. In particular, this refers to requirements for building lines and for materials which are permitted as exterior finishing’s for buildings. The requirements in the National Building Regulations are there for technical reasons, but what is technically acceptable might not necessarily be acceptable for other reasons.

SANS 10400 consists of the following parts, under the general title “The application of the National Building Regulations”:

Part B: Structural design

Part C: Dimensions

Part D: Public safety

Part F: Site operations

Part G: Excavations

Part H: Foundations

Part J: Floors

Part K: Walls

Part L: Roofs

Part M: Stairways

Part O: Lighting and ventilation

Part P: Drainage

Part Q: Non-water-borne means of sanitary disposal

Part R: Stormwater disposal

Part S: Facilities for persons with disabilities

Part T: Fire protection

Part V: Space heating

Part W: Fire installation

Part XA: Energy usage in Buildings

Standards are available from the SABS – Contact Standards Sales by telephone (012 428-6883), fax (012 428-6928), or email (sales@sabs.co.za)