Chapter 7

BUILDING ADMINISTRATION AND ORGANISATION

Introduction

Building Administration

The Role Players

The National Home Builders Registration Council (NHBRC)

Introduction

This section covers the administrative and organisational functions that require planning throughout the building process. In the broader sense of the building industry, many of these functions are often overlooked as they are only thought to apply to formal commercial projects. Although in smaller projects many of these functions could be limited or determined as irrelevant, they should nonetheless be applied, even if only to the extent required. With no intended difference to the meaning, we have used the word contractor and builder randomly in the text that follows. Although to some traditionalists, it could be said that there is a difference; a builder is somebody who does all the work himself or employs all his own tradesman; while a contractor is someone usually a company who employs his own professional site personnel and subcontracts the trades to others.

The iron law of a project life cycle

A building project’s limited duration implies a distinct project life cycle. Projects have beginnings, middle periods, and endings. In construction, the project life cycle goes through a number of distinctive phases, which can be defined as follows: feasibility and preliminary design, detailed design, construction, and the handover phase; and where most problems experienced are caused by not understanding the project life cycle and these phases fully.

All life cycles, without exception, are subject to the iron law of a life cycle: problems downstream are symptoms of neglect upstream. In other words, the problems you experience today are symptoms of things that you neglected earlier (Nel.2007:268). Administrative and organisational functions are generally upstream functions, executed throughout the normal construction project life cycle. It is therefore well worth developing a project life cycle that encompasses and highlights the topics discussed in this section.

Building Administration

Outline

Through the duration of a building project, big or small, informal or formal, everyone involved will to some extend be required to perform certain administrative tasks, and therefore needs to have a broader understanding about this subject. In this subsection, we explain the administrative function and process as briefly as possible. The topics are more or less generic, and the process usually follows a logical sequence, beginning with the tendering process. However, the process does depend on the size and type of building project, and as a result could differ from project to project. Like many other industries, everything is interrelated, where the people involved must work together regardless of their task or purpose, in developing plans that will maximise efficiency and productivity in achieving project objectives, and when these administrative functions are ignored, the project will undoubtedly run into difficulties of some sort.

Tendering

Tendering, often referred to as quoting, or offering a price to do something, is where an estimated value in monetary terms, is calculated based on the drawings and or other documentation provided to complete a specific trade, works, or even an entire building. These tenders or offers are usually requested by the employer or client or his agent, and may be required from one particular builder, or from a selected list of contractors, or specialised tradesman, or from the entire building industry. The tender (quote) is then usually offered in writing to perform such work to the employer or client at a specific price and on certain conditions and only when this offer (tender) is accepted does a contract come into being.

Pre-tender planning

In addition to the direct costs estimated for the work to be performed when preparing a tender, the estimate must take other factors that could have an effect on the final cost into consideration. For example, what resources are required vs. what resources are available; timing; durations; site conditions; temporary services, etc.

Documentation required when tendering

The discussion here is about the documentation required to estimate or price, as accurately as possible, a particular job or project, and not on the tender documentation itself. In larger or commercial type projects, a bill of quantities is usually the only document provided for tendering purposes, although the drawings, details, and specifications, would also generally be provided.

Unfortunately, in smaller type projects the information provided is usually limited, resulting in the builder or subcontractor having to make a number of assumptions; consequently inaccurate estimates are then made, which leads to discrepancies once the job or project starts.

Thus, the more comprehensive the information and the more detail you have the more accurate your estimate will be.

The following documentation should be made available as a minimum where no bills of quantities are available (see contract documentation for more information):

- Nature and scope of the work to be performed – for example a double storey building would require more scaffolding than a single storey building.

- Location of the site and any special conditions that need to be taken into consideration.

- Copies of all drawings.

- Copies of all details (if required) showing special or detailed work.

- A specification describing the materials and finishes required.

- A list of PC sums and allowances the client or employer wants included in the tender for example, allowances for sanitary-ware or light fittings – (these are amounts for materials whose exact details have yet to be determined).

- Nominated and selected subcontract amounts for example, supply and installation of the kitchen units.

- A list of other conditions, like contingency sums, durations, penalty clauses etc.

Tendering using a bill of quantities

On larger type building projects it is customary to engage the services of a quantity surveyor who then prepares a bill of quantities for the project, in which all the materials, labour and anything else that could have an effect on the cost of carrying out the work, is measured and scheduled. This bill then simply needs to be costed out by the contractor or builder using their rates, and when all the various items have been totalled together; it provides an accurate total estimate of costs. The tenderer usually requires nothing further for the preparation of the tender.

Tendering using a schedule of rates

Another form of tendering is for the client or his agent to prepare a carefully detailed schedule of rates of typical activities that are likely to occur on a particular project without providing quantities. The contractor or builder then simply offers rates (pricing) for these given items as described in the schedule.

This method or process is usually used only when pricing is required urgently. It is not a recommended way of tendering as it has a two distinct weaknesses:

- It is difficult to determine the overall value of the project and in turn its size.

- It is difficult from this to quantify the profitability of the project, as this can only be determined once the work is measured.

This method can however be used quite effectively as a preliminary bill to award a tender before a bill of quantities is available; especially when fast track type projects are being negotiated.

Methods of inviting tenders

Open tendering

This method of inviting tenders is often used by government departments, like local authorities, the department of public works, etc. and usually attracts a large number of tenders. This form of tendering can be very costly for unsuccessful tenderers and because the chances of success are often statistically small, this process is unattractive to many established contractors. A further drawback is one often ends up competing against chancers who are desperate for work and usually submit pricing that is unrealistically low.

This method is the most popular method of securing tenders for building projects; the process involves the employer, client, or agent approaching short list of six or eight contractors or subcontractors, who have been chosen because of their suitability to the type of project and have a sound track record.

The Building Contract

The building contract is an agreement between two parties, one of whom, the builder, tradesman, or subcontractor, agrees to erect a building or perform a specific job or trade, and the other, the employer or client agrees to pay for it. A contract comes into existence on the acceptance of an offer for work, which can be defined with the construction of new buildings, alterations and additions, renovations, or a specific trade. This acceptance of an offer implies an agreement between the parties, which is legally binding. A verbal contract is perfectly valid and is legally binding, although it is always recommended that any building contract be committed to writing; otherwise trying to prove the terms of a verbal agreement between the parties, should things go wrong, can be difficult. In the private sector, the most commonly used contract for residential buildings is the fixed price or lump-sum contract.

While in the commercial sector, contracts generally take the form of lump-sum contracts with bills of quantities, or with fast track projects, contracts with provisional bills of quantities can be used. These building contracts in the private sector are often concluded by not going out to tender, but as a result of direct negotiation in the form of offers and counter-offers being negotiated between the contractor and employer, and only when final agreement is reached between the parties, could one then say a negotiated contract has then been concluded. In the public sector almost all contracts go out to tender (open tender) and are so advertised to permit anyone who wishes to do so, to submit a tender, and typically take the form of only lump-sum contracts with or without bills of quantities.

Types of building contracts

Lump-sum contract

A lump-sum contract is where the builder submits a ‘fixed’ tender or price, based on the drawings and documentation provided, to supply all the necessary labour and materials and to perform all the work required from the erection to completion of a project in all respects. The success of a lump-sum contract depends largely on the amount of comprehensive information and detail provided beforehand i.e. before any work commences. One disadvantage of a lump sum contract from a client’s point of view lies in its inflexibility. There is no convenient basis, as with a contract based on a bill of quantities, for valuing progress or variations. Leaving the contractor in a strong bargaining position to charge what he wants for variations, resulting in the client being reluctant to make any changes, even if required. On the other hand, from a builders point of view, this would be desirable as the disruptive effect of any changes during the course of the contract is kept to a minimum. This type of ‘fixed price’ contract is more suitable for smaller type projects and not for large projects.

This type of contract also requires that the builder performs all the work supplying all the materials and labour to erect and complete a building, except that a bill of quantities is introduced and forms part of the contract. This type of contract has become the accepted basis for inviting tenders for larger type projects. There are a number of advantages that come with using bills of quantities for tendering, for example:

- All tenderers tender on the same basis, in other words one is comparing apples with apples.

- Bills of quantities are very accurate.

- Bills of quantities can form the basis of pricing variations and valuing work in progress.

There are also drawbacks when using bills of quantities; they can extend the pre-contract period, as they can only be prepared when all the technical documentation is substantially complete; and the added cost of further professional fees for the client.

This type of contract came about to eliminate the problem of the extended pre-contract period when using a contract with bills of quantities, and is used extensively in larger fast-track private sector projects. The provisional bill is produced from the designers preliminary sketches or concept drawings; in other words before working drawings have been completed. The main advantage in using this type of contract is ‘time’ – tenders can be invited sooner and the contract can actually be placed while the working drawings are still being prepared. The measurements are therefore only approximate and the entire bill is regarded as provisional and subject to adjustment when the final drawings have been produced and the work has been remeasured (Finsen.2005:23). The obvious disadvantage in using this type of contract lies in that the tendered amount is not an accurate forecast of the ultimate future cost of the work(s) or building(s), which can be further affected by the complexity of the work or building.

Another disadvantage is that the building work usually starts before all the drawings have been completed. Placing enormous pressure on the design team as the work progresses, this can result in the work actually being delayed while drawings are being completed. Furthermore, ill-considered decisions can then often be made because of the lack of information.

This type of contract is one where the builder is reimbursed for the actual cost of all labour, materials, and other expenses related to a project, together with an agreed management fee, which is usually expressed as a percentage of the direct costs. The management fee that is charged has no fixed industry norm, and is more about negotiation based on the size and nature of the project among many other considerations. One distinct disadvantage of this type of contract is that in reality the contractor can take advantage of the employer and use more expensive materials than required or work wastefully with the sole objective of increasing the cost so the benefit in fees is greater. Thus, this type of contract is not a popular choice, especially in higher value projects, although for low value smaller type jobs that require specialised trades or particular skills it can be used successfully.

This type of contract is sometimes used in the informal sector of the building industry where the contractor is undercapitalised. The builder undertakes to erect and complete the buildings for an agreed fixed lump-sum ‘labour-only’ price, while the materials are supplied by the client or employer. A clear distinction needs to be drawn between this form of contract and one in which the contractor undertakes to carry out the work for a remuneration of an agreed sum of money per day, week or month. If it has been agreed that he be paid on a time basis for performing the work instead of an amount for the total quantity of work involved in the project, he becomes an employee and not an independent contractor (Finsen.2005:26).

The difference here is significant in terms of risk and who is ultimately responsible, from supplying plant to insurance, workmen’s compensation etc. If the builder or contractor becomes an employee, the employer then assumes these responsibilities, and becomes the contractor by default.

This type of contract arrangement commonly termed or known as ‘owner building’ is where the owner (the employer or client) dispenses with the services of a builder and employs a range of tradesmen or specialist contractors to perform the required work.

These tradesmen and specialist contractors would usually be subcontractors to a builder, but as there is neither a builder nor general building contract in place, they are in fact independent contractors. The owner builder believes a contractor simply employs subcontractors to do the work and then adds a management fee and profit to their price. Therefore he or she believes the same can be done and thus save money. However, the owner builder never considers his or her own time and efforts that will be required in coordinating this type of arrangement, which can be substantial. The problems inherent in undertaking a building project in this manner are so great, particularly in the hands of the inexperienced, that it is an option that should be considered only for the simplest and least complicated projects (Finsen.2005:27)

Building contracts can be as simple as a single page document; for example, it would be a pointless exercise in having a lengthy contract document drawn up to fit a single window frame, or fit a garage door. Conversely, a single page contract document to build a million rand home would simply be inadequate.

One could therefore conclude that the contract should match the project, i.e. the scope of work, building size, duration, and the complexity; the contract also needs to provide sufficient assurances to suit both parties. In addition, no matter how well a contract may be legally written to suit a project, it is incomplete without specific information. This information, and most importantly, the specification, drawings and if being used the bill of quantities, or bill of resources, as discussed earlier, must form part of the contract. One needs to ask three questions to determine if the contract documentation covers the basics.

- What needs to be done?

- How much will it cost?

Has the contract amount been agreed and have the prime costs and provisional sums been included. Finally, has it been agreed upon how these amounts will be paid and when? - How long with it take?

A contract must be specific in terms of duration, i.e. have a start and completion date; and make allowances for extensions of time and penalties.

The specification, drawings and a clear description of what must be done (the scope of work) and the prime cost and provisional sums must be agreed upon and form part of the contract

There are various types of contracts to suit different circumstances available to the building industry. The JBCC Series (Joint Building Contracts Committee) contracts are recommended. They are available from the NHBRC (National Home Building Registration Council), MBA (Master Builders Association) and through the JBCC website. The CIDB (Construction Industry Development Board) have also developed various contracts that are recommended.

Although contracts will vary in content, the following items should generally be included in a building contract:

- Full names and addresses of the parties. The address that the parties have chosen where all notices of processes arising out of the contract may be validly delivered.

- Nature and scope of the work to be performed.

- Location of the site and any special conditions that need to be taken into consideration.

- A bill of quantities or provisional bill of quantities; or a bill of resources – annexed to the contract

- Specification – annexed to the contract.

- Working drawings and schedules – annexed to the contract. The drawings should be approved by the local authority.

- The contract amount and a schedule of how and when this amount will be paid; and if a deposit is payable this should also be included in the contract document.

- Prime cost (P.C) amounts – sums of money included in the contract sum for materials and goods to be obtained from a supplier and to be installed by the contractor; for example light fittings.

- Nominated and selected subcontract amounts (Provisional amounts) sums of money provided for nominated subcontractors, selected subcontract amounts, budgetary allowance, or any other monetary provisions, must be included in the contract.

- Extraordinary costs payable – must be listed and the party responsible for the payment stated; for example, connection fees, NHBRC contribution and plan approval costs.

- Commencement and completion dates – the duration of a contract would usually exclude the December holiday period, which is traditionally the builders’ holiday period.

- Penalty clause – It is common practice to stipulate a penalty clause in the contract document for late completion; the penalty should be a reasonable amount, but at least equivalent to the cost of alternative accommodation or lost rent/income.

- Variations – when variations occur, a method must be agreed on how the contract price and duration will be affected.

- Extension of time – if the contract has allowed for and extension of time, circumstances leading to the delay must be specified; for example, inclement weather.

- Insurance – the parties must agree who is responsible for the various insurances; for example, public liability, theft, etc.

- Retention – this has always been a contentious issue. If a reasonable amount is held for a reasonable period then retention should be in every contract.

- Defects Liability – it must be agreed by the parties what patent or latent defects the contractor will be responsible for and for what duration of time.

- Default and cancellation – the contract must clearly define how the contract can be cancelled if one party defaults. The employer’s default is usually because of non-payment and the contractor’s default because of non-performance.

- The contract should constitute the entire agreement between the parties and no alteration or addition thereto shall be of any force or effect unless reduced to writing and signed by both parties.

- The contract must be signed by both parties and witnessed.

Contract document terminology

Agent

The person or entity named in the contract or schedule appointed by the employer to deal with certain aspects of the project (see principal agent).

Bills of quantities

The document describing the measured materials and labour needed for a particular project.

Bills of resources

A document detailing the quantity and description of materials and labour needed for a particular project.

Calendar days

The twenty-four (24) hour days commencing at midnight (00:00) of the calendar i.e. weekdays and weekends.

Certificate of final completion

The certificate issued by the employer or principal agent to the contractor declaring the date on which final completion of the project was achieved.

Certificate of practical completion

The certificate issued by the employer or principal agent to the contractor declaring the date on which practical completion of the project was achieved.

Certificate of works completion

The certificate issued by the employer or principal agent to the contractor declaring the date on which works completion of the project was achieved.

Construction period

The period commencing on the date on which possession of the site is given to the contractor and the date on which practical completion will be achieved.

Contract documents

The documents that form part of the contract; for example, project drawings, bills of quantities, specifications, and any other documents that are required to describe the scope of work.

Contract sum

The amount accepted by both parties of the tender or negotiated amount that is stated in the contract.

Defect

Any aspect of the works that in the opinion of the employer or principal agent is not according to the contract or generally accepted good building practices (see latent and patent defects).

Drawings

The drawings and upon which the price and other details were determined for the project; these drawing form part of the contract.

Employer

The person or entity contracting with the contractor or builder for the execution of the works as covered in the building contract.

Final completion

The stage of completion where, in the opinion of the employer or principal agent, the works are free of all defects.

Instructions

A written instruction signed and issued by the employer or under the authority of the principal agent to the contractor.

Latent defect

A defect that a reasonable inspection of the works by the employer or principal agent would not have been visible before the issuing of a defects list (snag list).

Materials and goods

The materials and goods delivered to the contractor or his subcontractors for inclusion in the woks whether stored on or off site or in transit (production) but not yet part of the works.

NHBRC

The National Home Registration Council.

Nominated subcontractor

A subcontractor executing work provided for in a nominated subcontract amount included in the contract sum.

Patent defect

A defect that appears before the issuing of a defects list (snag list); which would mean the defect would be included in the defects list.

Payment certificate

A document issued by the principal agent usually the quantity surveyor certifying the amount due and payable by the employer to the contractor; for example a progress payment.

Practical completion

The stage of completion where, in the opinion of the employer or principal agent, completion of the works has substantially been reached and can effectively be used for the purpose intended.

Preliminaries

The priced items listed in the Preliminaries document with any additions, alterations, or modifications, forming part of the contract documents.

Prime cost amount

An amount included in the contract sum for materials and goods to be obtained from a supplier as instructed by the employer or principal agent and to be fixed/ installed by the contractor. If after purchasing an item, the amount spent exceeds the prime cost amount allowed in the contract, then the employer will be liable for the difference. The amount payable will be paid by the employer to the contractor on presentation of the suppliers invoice. If the amount spent is less than the prime cost amount allowed in the contract, the contractor will credit the contract amount with the difference.

Principal agent

The person or entity appointed by the employer and named in the schedule or contract (see agent).

Programme

A diagrammatic representation of units of works indicating the dates of commencement, stage completions, practical completion, and final completion of a particular project.

Retention

The percentage selected by the parties to the building contract, by which each progress payment will be reduced, this amount is then held by the employer until such time final completion is achieved by the contractor; the retention would then become payable by the employer to the contractor.

Schedule

The listed variables applicable to a particular project which forms part of the building contract.

Selected subcontractor

A subcontractor executing work provided for in a selected subcontract amount included in the contact sum.

Shop drawings

Drawings, diagrams, designs, illustrations, schedules, performance charts, brochures, setting out drawings, shop details and other data which are prepared by the contractor or subcontractor or any other party which illustrates manufacturing details, fixing instructions and methods of execution of work.

Site

The land or place on, over, under, in or through which the works is to be executed.

Working days

The twenty-four (24) hour days commencing at midnight (00:00) excluding weekends, public holidays, and any annual shut down period.

Works

The works described in general terms detailed in the building contract.

Works completion

The stage of completion where, in the opinion of the employer or principal agent, the work on the works completion list has been completed.

Contract Administration

This topic or task discusses who is responsible for the administration of the contract; in larger projects, this is usually the responsibility of the principal agent or other agents as appointed by the employer or client. In smaller residential type projects, a principal agent is very seldom used, some might use a project manager or the architect, but in most instances, the employer (homeowner) assumes the responsibility for the proper administration of the contract.

These responsibilities come with a number of duties that require execution to ensure the proper progress of building work; some of these duties include:

- Meeting with the contractor on a regular basis to inspect and facilitate the progress of the works.

- Record all actions taken by the parties including site meetings.

- Issuing of instructions and drawings.

- Attend to decisions about variations and delays

- Selection of sub-contractors where required.

- Selection of materials covered under PC amounts

- Verifying work in progress and issuing payments.

These responsibilities go far beyond what the average employer (homeowner) envisages, and requires a lot of time and effort, and for the unskilled, it can become a major problem regarding the proper functioning of the contract and work progress. It is always recommend that the employer (homeowner) make use of professionals when it comes to the proper execution of contract administration.

Contract payments

Interim payments

Interim payments based on valuations prepared by the principal agent for work done at a given point, are usually prepared monthly by no later than a specified date and are repeated every month until the final payment. These valuations should represent the total amount of work carried out to date, including unfixed materials and goods procured by the contractor, less any amounts previously certified. While the obligation to prepare the valuation and issue the certificate rests with the principal agent, the contractor is required to assist him to determine the valuation by preparing and supplying a claim for payment incorporating measurements and valuations based on the bill of quantities of duly completed work, and material and goods, together with relevant documents such as invoices.

The valuation should incorporate the value of work done by the subcontractors and include materials and goods supplied by them. This payment method is used in all larger residential or commercial type projects.

Progress payments

Progress payments based on pre-determined milestones, are payments for work completed or progress achieved; for example, when the surface bed has been cast, or the roof has been installed, the contractor would then be paid the amount that was stipulated in the contract schedules. This type of payment method is used where no bills of quantities have been used.

This payment method is often used in smaller residential type projects.

The employer is obliged to pay the amount certified or pay the pre-determined progress payment within a reasonable time, usually seven calendar days of the date of issue of the certificate or the contractor providing the employer with an invoice for the amount certified or for the amount of the predetermined progress payment. Contrary to what many contractors assume, there is no provision in most building contracts that would entitle the contractor to suspend work if the employer fails to pay by the due date, nor is there provision to remove materials and goods from site. The contractor would need to compel the defaulting employer to honour the contract and seek other remedies; for example, place the employer on terms and should the employer still not pay the contractor could then have the contract cancelled and sue the employer for damages.

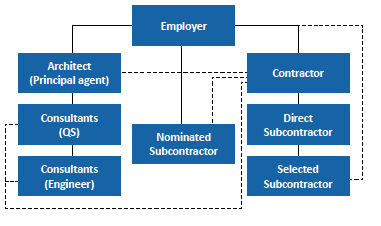

Subcontractors

The modern trend towards more and more specialisation in the construction industry, coupled with the tendency of many building contractors limiting themselves to only the so-called wet trades, (although there has been a steady increase in subcontracting even the wet trades) the number of specialist subcontractors in the construction industry has grown enormously over the last few decades. As this trend of subcontracting has developed, it has for various reasons seen the development of different ways of employing subcontractors; namely, nominated, selected and domestic subcontractors, and direct contractors – These different kinds of appointment are discussed in greater detail below.

Different kinds of appointment

Nominated subcontracts

A nominated subcontractor is a subcontractor that has been nominated to perform certain work by the employer or the employers agent, for which a monetary allowance, termed a nominated subcontract amount, has been included in the contract sum. Even though the contractor enters into an agreement with the nominated subcontractor as instructed by the employer, most building agreements contain provisions that absolve the contractor from liability for delays caused by the default of nominated subcontractors and for any additional costs that may be incurred when a nominated subcontractor defaults and has to be replaced.

The risk in hiring nominated subcontractors using this method of appointment lies with the employer, although the employer lacks the contractual nexus that would enable them to sue the nominated subcontractor for damages in the case of default. This has led to the introduction of the selected subcontract in an attempt to overcome this prejudice to the employer. The contractor is entitled to refuse to enter into a subcontract with a subcontractor who has been nominated by the employer or the principal agent for a number of reasons, which would usually encompass some of criteria discussed under the next sub-heading – Selected Subcontracts.

A selected subcontractor is a subcontractor who performs specific work, for which a monetary allowance, termed a selected subcontract amount, has been included in the contract sum. Unlike the process followed in appointing a nominated subcontractor, the contractor is entitled to participate in the process of inviting tenders for selected subcontracts and in selecting the successful subcontractor. The involvement of the contractor in the tendering process can be problematic if subcontracts need to be finalised and tenders invited before a contractor has been appointed, consequently the only solution to this would be to call for nominated subcontracts. In a practical sense, a selected subcontractor is no different to a nominated subcontractor except that the contractor, not the employer, accepts the risk of delays and additional costs caused by default and replacement. It is the responsibility of the contractor to establish whether the tenderer can meet the required contractual requirements, failing which, the contractor can provide reasons why he or she should not enter into a subcontract with the selected tenderer, and the process would then be repeated to find a suitable subcontractor.

Direct contractors are contractors who have been employed directly by the employer or the principal agent to perform artistic or specialised finishing work; for example, sculptures or fitting a home cinema. Provided that the type and extent of such work has been described in the contract schedules, the contractor is required to permit such work to be executed by these direct contractors engaged by the employer. The contractor is not responsible for these types of contractors in any way whatsoever, although such workmen are subject to the reasonable control of the contractor.

When selecting a subcontractor regardless of their speciality they must be chosen on the following criteria.

- Business integrity and guarantee of service

- Quality of workmanship that is suitable to meet the requirements of the specification.

- Financial stability

- Ability in meeting project completion dates and do they have the necessary resources to suit the size of the project.

- Investigate the details of what facilities the subcontractor would require and if these requirements suit the main contractor, especially in the case of nominated subcontractors.

1 In the event of the subcontractor defaulting or being declared insolvent, and depending on the way the subcontractor has been appointed, the employer, or the contractor, will be at risk.

Without going into too much detail here, a contract agreement between the subcontractor and contractor is basically the same as the building contract between the contractor and the employer. The important difference being, the agreement is reached between the contractor and the subcontractor, to perform a specific trade at an agreed price; the agreement furthermore records the agreed obligations of both parties.

It is also important to include whatever information is available in terms of specifications, drawings, details etc. to ensure there are no misunderstandings. There are various types of contracts to suit different circumstances available to the building industry. The JBCC Series (Joint Building Contracts Committee) contracts are recommended. They are available from the NHBRC (National Home Building Registration Council), MBA (Master Builders Association) and through the JBCC website. The CIDB (Construction Industry Development Board) have also developed various contracts that are recommended.

Subcontractor payments are usually included in the interim payment certificate submitted by the contractor to the employer. Provided that the subcontractor has furnished the contractor with an invoice. However, in terms of most building agreements, the contractor is not obliged to pay the subcontractor if the employer has not paid the interim payment certificate providing for such payment, provided the contractor gives notice to the subcontractor of the employers default. The contractor will only pay the subcontractor once receiving payment from the employer.

Unlike the contractor, the subcontractor is entitled to suspend work in order to enforce payment, provided the subcontractor has followed the procedures and provisions allowed for in the contract agreement entered into with the contractor. If the contractor has in fact been paid by the employer and fails to pay the subcontractor, the remedy most favoured by subcontractors is to get direct payment from the employer.

Administration

In order to maintain control over any productive process it is necessary to have a programme or integrative plan of all work activities required for the execution of a specific project, against which to compare the actual progress achieved. In its simplest form, a building programme may only state a proposed starting and completion date; this is clearly meaningless in the context of planning and control, and offers no help to the management of the building project. For a programme to be useful and offer meaningful information, it must first incorporate all the required activities, listed in the sequence in which they would be implemented, known as activity sequencing. Thereafter dependencies need to be defined, relationships between two or more activities; for example, plastering a wall cannot start before the wall has been started and built; it could also require that the electrician install conduits in the wall before the plastering activity can start. Once the activities have been determined, durations need to be applied to these activities. Durations are typically expressed in workdays and exclude holidays and other nonworking periods. Duration estimation should only be left to the experienced, using the following points as a guide:

- Subjective methods – expert opinion, where previous experience is used; the more the experience the more accurate the estimate will be.

- Comparable methods – Rules of thumb; similar activities are likely to have similar durations.

- Detailed methods – divide the activity into sub-tasks, then estimate each sub-task and combine the totals.

Programming provides management with a means of exploring the alternatives available in trying to achieve the most cost effective and efficient way of completing projects. Programmes also fulfil a number of other purposes, as discussed below.

Objectives

- To record the agreed intentions with the employer.

- To supply the timetable for coordinating, the issue of drawings and information, the placing of orders and delivery of materials, and resources like plant and subcontractors.

- To prepare a basis for the introduction of bonus payments by achieved outcomes.

- To show the sequence of operations and the total output rates required for labour and plant.

- To provide a yardstick in reaching certain milestones.

- To provide an overview of the likely cash flow implications.

- To demonstrate what the likely consequences will be if changes are made.

- To facilitate delegation

- The basis of effective control.

Project schedules

A project schedule is normally expressed as a chart or by some other graphical means of representation in which the subdivision of activities are normally shown on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis; with each operation indicated by a bar, the length of which is governed by the duration. See example on next page.

Schedule development

Schedule development involves determining the start and completion dates to each activity; this will in turn determine the entire projects start and completion dates.

The Gantt chart

The Gantt chart is a graphic planning and control method in which a project is broken down into separate activities or tasks. The activities are plotted as bars or lines on a timeline, with the starting and end dates of the activities indicated on the chart (see Example of a programme using MS Project). This allows managers to monitor progress of the project by comparing actual progress with planned progress.

The Programme Evaluation and Review Technique, is another planning tool that uses a network to plan projects involving numerous activities and their interrelationships. The key components of PERT are activities, events, time, and the critical path. PERT also allows management to monitor progress, identify possible delays, and shift resources to keep the project on schedule.

The critical path

Knowledge of the critical path in building is essential; the critical path determines the length of time it will take to complete a project. The critical path is the longest or most time-consuming sequence of events and activities in a PERT network. Remembering that any delay of an activity on the critical path will delay the project completion time. Thus, the critical path determines the completion date. The critical path is usually determined by using a software project planning application for projects involving copious activities; it can however be done manually with projects where fewer actives are involved.

Planning

The plans discussed here are operational plans and the basis of effective planning is programming. Operational plans are narrowly focused and have relatively short periods (monthly, weekly, and day-to-day). For example, the site agent will formulate a weekly operational plan ensuring all the required subcontractors are available for the following weeks planned activities.

There are two basic forms of operational plan, namely single-use plans and standing plans. Standing plans are plans that remain more or less the same for long periods of time; for example polices and standard procedures and methods. While single-use plans are used for non-recurring activities, like programmes used in building projects. A programme is a single-use plan for a large set of activities. In larger type projects, the programme can even consist of a number of different projects within the main project, each requiring their own project plan.

A project plan is formulated to guide a project and should clearly define the following objectives:

- The scope of work

- The projected duration of the project

- The budgeted costs allowed for the project

- The required level of quality

Objectives or goals form an integral part of planning; coordination of project goals is of vital importance if all the goals are to move the project in the same direction. Thus, the primary objective of planning is to find the most suitable way of coordinating activities with available resources, for the overall success of the project.

As discussed previously (the project life cycle) the normal building project goes through the following phases; feasibility and preliminary design, detailed design, construction, and handover. These phases require that operational plans be formulated to ensure that overall project objectives are achieved and a master project plan is available for the proper running of the project.With proper planning, the following can be achieved:

- Highlights what information is required before it is needed, ensuring uninterrupted progress.

- Acts as tool for the efficient allocation of resources.

- When site personnel, assist in the planning process the attendant responsibility for the decisions taken increases overall productivity and motivation.

- Enables management to review actual progress achieved and overall project performance and provides a means of taking corrective action when things are not going as planned.

- When time is gained, it can be re-programmed to advance the completion date.

Note: Project planning must be a continuous activity that is updated regularly and encouraged by management.

Communication

Effective communication is essential on a building project; everyone on and off site, continually receives and sends information. This information is processed in numerous ways. For example, issuing and interpreting drawings, giving and receiving instructions, recording the minutes of site meetings, using a computer to send e-mails, using the telephone, etc. Without this communication, nothing would happen.

For this reason, as part of the administrative function, it is important that proper communication protocols are established; that is, who should be talking to whom about what and what information is needed on site to complete the project.

Generally speaking, everyone at different levels of a typical] building project organisational hierarchy make different decisions, control different types of processes and therefore have different information needs; also remembering that organisational communication flows in four directions: downwards, upwards, horizontally, and laterally.

Communication is not only about speaking to one another; it includes written messages, like information provided in terms of drawings, specifications, schedules, etc. Therefore, gathering the right information, storing it so it can be used and manipulated as required and using it to achieve project goals, is essential.

What’s more, a lot of this information needs to be available on site to the people who need it for both decision-making and problem solving purposes. It is always recommended, especially for larger type projects, that computers with the correct technology in the form of hardware and applications software, be available on site, including printers, photocopying equipment and telecommunications.

Costing

Costing discussed here has nothing to do with the estimating function in determining a tender price; the costing discussed here represents the resources that have to be used to achieve a project objective. The costs incurred when building a home or any other structure may be classified in various ways and one important way is according to how they behave in relation to changes in the volume of activity.

A cost may be classified according to whether it:

- Remains constant (fixed) when changes occur to the volume of activity

- Varies according to the volume of activity.

These are known as fixed costs and variable costs respectively. For example, a site manager’s salary would be a fixed cost while the cost of the bricks and mortar would be a variable cost.

Fixed cost

Fixed costs are only costs that are unaffected by changes in the volume of activity, although wages are often assumed to be a variable cost but in practice they tend to be fixed, unless wages are paid according to how much output they produce. Some common fixed costs include:

- Rent

- Insurance

- Salaries and Wages

- Motor vehicle lease payments

Variable cost

Variable costs vary with the volume of activity. Most activities on a building project are production activities; consequently, variable costs usually make up the bulk of total cost. Some common variable costs include:

- Cement used to make the mortar

- The cost of laying the bricks in the wall (if volume based)

- Fuel cost to run generators on site

Costing objectives

Costing is responsible for keeping records associated with accounting for labour, plant, materials, overheads, etc. Costing must not only record the actual costs but also analyse the costs of production so costs can be managed in accordance with what was priced.

A typical building projects expenditure is extremely diverse, but can be grouped into the following cost categories:

- Direct labour paid in the form of wages and salaries to the contractors own employees.

- Plant and equipment expenses, including running costs like fuel, oil, spares, cutting discs, etc.

- Overheads such as temporary services like toilets, office space, storage, and telephone costs, insurance, traveling expenses, meals etc.

- Building material purchases; including both fixed materials and consumable materials like shuttering and formwork.

- Subcontractor payments.

- Percentage of the contractors (off site) office expenses.

There are four broad areas of why costing is important and where contract managers can use this information for better decision-making:

- Pricing and output decisions – Having cost information helps management make decisions on prices to be charged.

- Exercising control – Managers need cost information to help them keep the project on course and by ensuring costs progress as budgeted.

- Assessing relative efficiency – Cost information can help managers compare the cost of doing something oneway, with its cost if done a different way. For example, using ready-mix concrete as opposed to site-mix concrete

- Assessing performance – The level of profit generated over a period is an important measure of project performance.

Cost units

We cannot have costs unless there are items being costed. A cost unit is one unit of whatever is having its cost determined, usually one unit of output of a particular product, service, or time. These cost units may be – a unit of production e.g. m2 of brickwork or a unit of service e.g. man hours worked.

Types

To provide full cost information, we need to have a systematic approach to accumulate the elements of cost and then assigning this total cost to particular cost units on some reasonable basis. The starting point is to separate cost into two categories: direct cost and indirect cost.

Direct cost

Direct cost is the type of cost that can be identified with specific cost units. The main examples of a direct cost are direct materials, labour and equipment costs. For example, in determining the cost of building a wall, both the cost of the materials used in building the wall and the cost of the labour to build it would be part of the direct cost of that cost unit. Collecting elements of direct cost is a simple matter of having a cost recording system that is capable of capturing the cost of direct materials used on each project and the cost, based on the hours worked and the rate of pay, of= direct workers, or the payments to subcontractors for doing such work.

Indirect cost

Indirect cost or overheads include all other elements of cost, those items that cannot be directly measured in respect of each particular cost unit. For example, the water used in the mortar would be an indirect cost of building the wall.

Note: Direct/indirect is not linked to variable/fixed.

Methods

Costing methods must suit the requirements of the project, and for this reason, there is no one method that suits all, although job costing is the more conventional method used.

Unit costing

This method is used when the cost units are identical. Cost units that are identical must logically have identical costs, and this concept of equality of cost is the basic feature of unit costing. The basic computation in all unit costing will therefore be – (Total cost ÷ Number of units).

Standard costing

A comparison of actual cost with a predetermined standard cost. Where the cost of any deviations (variations) is analysed by causes. This method allows management to investigate the reasons for these variations and to take suitable action.

The term job costing is used to describe the way in which we identify the full cost per cost unit (unit of output) where the cost units differ. To cost a particular cost unit, we first identify the direct cost of the cost unit, which is normally fairly straightforward. We then seek to ‘charge’ each cost unit with a fair share of indirect cost (overheads).

It is important to note that whether a cost is direct or indirect depends on the item being costed – the cost objective. To refer to indirect cost without identifying the cost objective is incorrect.

It cannot be emphasised enough that there is no ‘correct’ way to allocate overheads to jobs. Overheads, by definition, do not naturally relate to individual jobs. One way in dealing with indirect cost is by using the cost centre basis; where overheads are accumulated and then charged to those cost units to which provides a service. A cost centre can be defined as a particular physical area or some activity or function for which the cost is separately identified. To see how job costing works, let’s consider the following simple example. Easy plumbers, a business that provides a plumbing contracting service, has overheads of R15 000 each month. Each month 800 direct labour hours are worked and charged to cost units (jobs carried out by the plumbing business). A particular plumbing job undertaken by the business used direct materials costing R400. Direct labour worked on the job was 2 hours and the wage rate is R100 an hour. Overheads are charged to jobs on a direct labour hour basis.

What is the full cost of the job?

First, we must establish the overhead absorption (recovery) rate, that is, the rate at which individual jobs will be charged with overheads. This is R18.75 (total monthly overheads (R15 000) ÷ monthly direct labour hours (800) per direct labour hour).

| Direct materials | R400.00 |

| Direct labour (2×100) | R200.00 |

| R600.00 | |

| Overheads (2×18.75) | R37.50 |

| Full cost of job | R637.50 |

Explanation

This costing section has merely been written to illustrate the need for costing and the importance thereof but it must be appreciated that the subject of costing is a complex one and a subject on its own; it is therefore not the aim of this section to provide a comprehensive study on costing. The application of correct costing techniques often requires the assistance of a professional and the reader is advised to seek proper assistance and guidance in this regard.

Site administration

Site representative

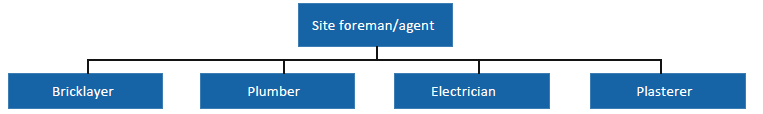

It is normal practice that a building contractor would have a representative on site at all times. This individuals primary function is to ensure the proper day-to-day running of the site from progress, to taking and carrying out instructions. Traditionally, the contractors representative on site was a site foreman, normally an artisan with a number of years of general contracting experience. This is seldom encountered today; the foreman’s place has been taken by a variety of site agents, contracts managers, and clerks who attend to the various aspects of the administration of a building project. Regardless of the individuals title, the responsibilities of the site representative remain the same and include the following:

- Setting out the works

- Ordering materials

- Coordinating the work of the various trades and subcontractors

- Keeping and updating the site diary

- Taking instructions from the employer’s agents

- Ensuring the quality of work meets the required standards and specifications

Building regulations

Building regulations regulate the design and construction of buildings by providing minimum standards established to safeguard the life, health, property, and general welfare of the public. Their intent is to establish minimum deemedto- satisfy and functional requirements in terms of design, structural strength, sanitation, adequate light and ventilation, energy conservation, and safety from fire and other hazards. Building regulations in South Africa are known as the National Building Regulations (NBR) and are covered under the SANS 10400 suite of standards. These standards provide a basis upon which designers and engineers design buildings and material and equipment suppliers fabricate products.

Extracts from SANS 10400

The National Building Regulations do not purport, and were never intended, to be a handbook on good building practice. They set out, in the simplest and shortest way possible, requirements to ensure that buildings will be designed as safe environments.

In order to understand and interpret the National Building Regulations correctly, it is important to understand the philosophy and intent behind the Regulations. One aim of the drafters of the Regulations was to keep the number of Regulations to a minimum. It was therefore decided that, as far as possible, the Regulations should be concerned only with the health and safety of persons in a building, that all technical aspects should be covered by functional regulations and that the Regulations should be written in such a way that they assist rather than impede the use of innovative building systems and designs. This philosophy was taken a step further in the current amendment of the interpretation of the regulations by introducing the concept of two different types of buildings to cater for different user needs and expectations.

Part A: General principles and requirements

Part B: Structural design

Part C: Dimensions

Part D: Public safety

Part E: Demolition work

Part F: Site operations

Part G: Excavations

Part H: Foundations

Part J: Floors

Part K: Walls

Part L: Roofs

Part M: Stairways

Part N: Glazing

Part O: Lighting and ventilation

Part P: Drainage

Part Q: Non-water-borne means of sanitary disposal

Part R: Stormwater disposal

Part S: Facilities for persons with disabilities

Part T: Fire protection.

Part U: Refuse disposal

Part V: Space heating.

Part W: Fire installation.

Part X: Environmental sustainability

Part XA: Energy usage in buildings

A number of these standards are discussed in greater detail throughout this book. This information is intended to provide the reader with an insight into this important information and to impart a better understanding of the standards available and their content and we urge all readers to obtain a copy of the standards from the SABS; only an entire copy of the SANS 10400 suite will provide a complete understanding of these standards.

SABS – Standards Division

The objective of the SABS Standards Division is to develop, promote and maintain South African National Standards. This objective is incorporated in the Standards Act, 2008 (Act No. 8 of 2008).

Amendments and Revisions

South African National Standards are updated by amendment or revision. Users of South African National Standards should ensure that they possess the latest amendments or editions.

Buying Standards

Contact the Sales Office for South African and international standards, which are available in both electronic and hardcopy format.

Tel: +27 (0) 12 428 6883

Fax: +27 (0) 12 428 6928

E-mail: sales@sabs.co.za

South African National Standards are also available online from the SABS website.

Local authority

In terms of section 7 of the National Building regulations and Building Standards Act, 1977 (Act No. 103 of 1977), a local authority is required to be satisfied that any application to erect a building complies not only with the requirements of the Act but also with any other applicable law. Where there is conflict between Regulations made in terms of the Act and regulations made in terms of any other Act the more stringent requirement shall prevail.

Each town or city has a local authority. The local authorities provide basic services like water, electricity, and refuse removal for people living in that town or city. Your local authority is the level of the government that is closest to you. Even though local authorities get some money from the central government to provide certain services, they must also raise their own money from rates, taxes, and service fees. Unless you pay for services, your local authority will not have enough money to provide these services. Everyone has to submit building plans. Any new building and any alteration that adds on to or changes the structure of an existing building must go to the city’s (Planning) Development Management Department for approval. If you make a change to the structure, for example, add on a carport, you need permission to do so. It is important to remember that the local building control officer needs to make various inspections before building starts and during the building process. Some local authorities differ concerning the number of these inspections, but they normally include:

- Trenches or excavations must be inspected prior to the placing of concrete for any foundation.

- Surface bed and poison

- Drainage installation

- Roof compliance

- Plumbing installation generally

- Electrical compliance

- When the building is completed – occupancy certificate

- Any fire installation

See Drawings for more Information on plan approval and the local authority.

Indemnities and Insurances

Building is a risky business. There is not only the everpresent danger of physical loss or damage to the works itself, but danger of harm to the people working on the site and to third parties on or off the site and to their property. For this reason contract works and indemnity insurance are recommend for any projects where risk is involved.

Contract works insurance

Most building contracts impose an obligation on the contractor to effect contract works insurance for a specified amount to be maintained until practical completion of the works is achieved, when the risk of loss or damage passes to the employer or owner. Contract works insurance is for the risk of loss or damage to the entire works, including the work performed by subcontractors, and is therefore unnecessary that subcontractors effect their own insurance. It is also quite common that such insurance policies may be taken out either by the contractor or the employer, the decision being taken as at the time of pricing and concluding the contract agreement. In trying to determine the amount of cover, there is no rule of thumb. It is recommended that not only the replacement cost be considered, but escalation, time, removing of the damaged works, additional professional fees, to name a few, be considered.

A building contractor, executing the works, may negligently cause injury to, or death of, a third party, or damage his or her property, and such third party would have the legal right to claim damages from the contractor.Public liability insurance is therefore required to cover the risks as described above, and can be taken out either by the employer or the contractor. Most contract agreements, holds the contractor liable for these public liability risks, and indemnifies the employer against any claims in this regard; which also applies to subcontractors, who would indemnify the employer and the contractor against any claims from his or her own negligence. Furthermore, It is required that the contractor and subcontractors take out insurance in terms of the Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases (COID) Act 130 of 1993 to indemnify themselves in respect of claims made by employees who sustain injuries or disease as a result of their employment on the works.

See Health and safety in this section for more information.

A contractor will usually purchase plant when the scale of operations and site conditions permit. Careful record must be kept to ensure that none of this plant (assets) is or improperly disposed of and that the contract is duly charged for the use of such plant. A plant register should be kept and careful records maintained of all movement between sites and/or yards.

Materials

Materials used in construction should be free from defects and it is a term implied by law that the building contractor is deemed to be an expert in building, and is expected to ensure that the materials he uses for the works are not defective. The contractor also warrants that the materials that he uses will be fit for their purpose, and if not, the contractor is obliged to replace these materials with suitable materials. The warranty of fitness for purpose is excluded where the contractors freedom of choice is removed by any specification of such materials laid down by the employer or his or her agents.

Contractors who contract for the erection of residential units are required by the Housing Consumers Protection Measures Act, 1998 (Act No. 95 of 1998) to register as home builders with the National Home Builders Registration Council (NHBRC). Only registered builders may construct houses and all houses shall be enrolled with the NHBRC, who in turn provide a five-year warranty protection against major structural defects in new homes. In order for the NHBRC to be able to manage the risk involved in providing such a warranty, it has been empowered to require home builders to adhere to a range of construction requirements described in their Home Builders manual aimed at ensuring acceptable levels of structural performance, which includes materials in terms of performance criteria, and quality.

This legislation is intended to safeguard the interests of home owners, more particularly those who do not employ architects or other professionals as principal agents but deal directly with the contractor on his or her own terms.

Employers are bound by legislation to follow and to abide by The Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Act, 1993 (Act No. 85 of 1993) to ensure a safe and healthy work environment for their employees; the building industry is no different to any other industry, you have probably seen large boards outside construction sites displaying their accident statistics, if any, to show the public and their employees what has been achieved to prevent casualties. The construction industry is one of the most hazardous work environments and for this reason a thorough accident prevention and safety training programme must be implemented and maintained on all building projects. The OHS Act offers extensive guidelines to employers and employees for proper safety and health implementation. It covers a number of aspects from safety and protective clothing, lifesaving equipment, tool and equipment safety, fire protection and prevention, material handling, to signage and barricades required on site. The contractor is responsible for administering safety procedures on site and is duty-bound to appoint a health and safety representative. Workers must be trained in recognised safe working practices and the proper use of mandated protective clothing; for example, wearing hardhats and safety boots on site. Copies of the (current) OHS Act are required by law to be kept and displayed in the site office along with material data sheets outlining the hazards associated with certain construction materials and activities. It also the responsibility of the health and safety representative to ensure all safety equipment is properly maintained and undergoes regular inspections.

See Section 7 Safety & General Site Considerations for more details

The completion process

Completing the final finishing items to a building can be a lengthy and involved process, with small items of work still needing to be finished off, minor defects requiring rectification, and the installation of final fittings. It is commonly accepted that the employer or owner take occupation before this work is completed and will allow the ‘finishing off’ to proceed after occupation provided it doesn’t inconvenience the employer too much. The stage at which the works is sufficiently completed to make occupation possible and so determine that the building is usable or fit for purpose while the contractor ‘finishes off’ is termed substantial or practical completion.

Practical completion

Practical completion is a very significant milestone in the progress of the building contract. Besides the practical issues, practical completion is the date on which:

- The contractor’s liability to pay penalties for late or noncompletion ceases.

- Responsibility for the building passes from the contractor to the employer/owner.

- Retention becomes payable to the contractor by the employer in cases where retention has been held.

The contractor is required to notify the employer or agent in advance of the date on which he or she considers that the works will have reached practical completion to enable the employer or agent to make and complete an inspection of the works on or before that date. It is however important that the contractor inspect the works beforehand to satisfy himself or herself that the standard of work and the completion thereof is in accordance with what was specified and expected. In the case where the employer or his agent considers the works as not practically complete, he or she must issue the= contractor with a practical completion list (snag list) defining the incomplete and defective work that requires attention, in order to become practically complete. This procedure will be repeated until such time the employer or agent is satisfied that the works are practically complete and is prepared to issue a certificate of practical completion and a works completion list. The employer’s right to take occupation of the building on practical completion is however, subject to the issuing of a certificate of occupancy.

A certificate of occupancy is issued in terms of s14 of the National Building Regulations and Building Standard Act 103 of 1977 as amended. In terms of this provision, the local authority is required to issue such certificate within 14 days of being requested to do so by the owner of the building or any person having interest therein. The certificate is issued by the local authority indicating that the building is in compliance with locally adopted building codes and standards and local by-laws as determined when the drawing were approved and that the building is in a suitable condition to be occupied. Thus, before a certificate of practical completion can be issued the local building control officer must substantiate that all the work has been completed as per the drawings, and that the quality of workmanship meets the specified standards. All functional appliances like sanitary-ware, light fittings, and stove must have undergone testing and be working properly. The site must be cleaned, all surplus materials and temporary equipment or huts removed, and the surrounding street and sidewalks returned to their pre-construction condition.

The building control officer would also require certificates of compliance from the structural engineer, confirming that the work complies with statuary requirements, as well as certificates issued in respect of the electrical and plumbing installations which could also include the roof. It is commonly accepted that the contractor apply to the local authority for an occupancy certificate. It is also recommended that the contractor determine what criterion is expected from the local authority in terms of an occupancy certificate well in advance.

Works completion

Works completion may be defined or considered to be the state of the works where the work is complete in all respects and there are no apparent defects. This process follows practical completion in that the contractor now considers that the work specified on the works completion list has actually been completed. The process is the same as practical completion in the sense that the employer or agent would inspect the works, provided the work on the works completion list has been completed and issue a works completion certificate. If not this procedure will be repeated until such time the employer or agent is satisfied that everything on the works completion list has been completed and is prepared to issue a certificate of works completion.

Note: We use the term certificate (which can be defined as a record or document) as some building contracts provide for this and have actual forms available that only require completion when needed. Where no certificates are available this process can be successfully undertaken using one’s own documentation.

Defects liability period

Let’s first try and define what is a defect – A defect can be defined as any aspect of the works which, in the opinion of the architect or other competent person, is not according to what was agreed, including any imperfection that impairs the structure, composition or function of any aspect of the works. The contractor remains liable to remedy at his or her own cost any defects in the works that may become apparent within a specified time; usually a period of 90 calendar days from date of works completion for final completion. This defects liability period can also extend far beyond 90 days in terms of common-law, where one can remain liable for latent defects for all time, or at least until the building is demolished. However a commonly accepted rule of thumb on large commercial projects is five years from date of final completion. While this period seems very long, in practice it is often very difficult to say with certainty that a defect is due to the contractors failure to carry out the work in accordance with what was expected or even good building practice; it is also impractical to imagine that many building contractors building residential homes will still be in business in five years.

The Role Players

Outline

The role players involved in the building of the average residential building are often only thought to include the parties to the building contract – the owner or employer and building contractor. However, during the normal course of building there are other role players who are charged with many duties as agents or as a service to the owner or employer, for example the architect, the project manager, the engineer, etc. as discussed below.

The Employer/Client

Employers/clients can be divided into two distinct categories; those who erect buildings for their own ownership and use, whether they intend to inhabit and use the buildings themselves or let them to others; and those who sell the buildings so they can recoup their capital, with a profit, and embark on the next project, this type of employer is generally referred to as a property developer. The need that these different types of employer/client have for the use of professional services like architects, engineers and other consultants varies considerably. For example, there is the prospective homeowner who needs advice and assistance almost in every way throughout the duration of a building project. While the property developer is usually familiar with all aspects of the building process, and can even have within their own organisation architects and other specialists to carry out the work of these role players, or who may engage independent consultants appointed for specific projects only.

The Contractor/Builder

A building contractor usually undertakes to build the entire project, moving onto a vacant site at the inception of the contract, and at its completion delivers a building that is complete in all respects and ready for occupation and use by the client/employer. The building industry is traditionally divided into a number of trades; such as bricklaying, carpentry, plumbing, plastering and painting. A building contractor employs subcontractors and workmen from various trades to carry out the work of the building process. Building contractors range from one man businesses to large national organisations. The small contractor takes on the challenges of a highly complex industry with minimal resources. In the residential market, the contractor generally wears the hat of the salesman, quantity surveyor, accountant, buyer and project manager. Very little professional assistance has been used by smaller contractors in the past and in particular the assistance with pricing a project accurately. The success or failure of a contractor depends largely on his ability to quote profitably and work efficiently. Bearing in mind that a contractor will usually quote a fixed or lump sum contract price, which generally includes materials and labour, where the margin for error is very small. If a contractor has not allowed for overheads in the contract price, a percentage mark-up can be applied to the contract price to accommodate for these costs. The profit is dependent on, to name a few, market conditions, complexity of the work and the risk involved. The contractor should concentrate more on establishing an accurate cost and then applying what he feels is a reasonable profit.

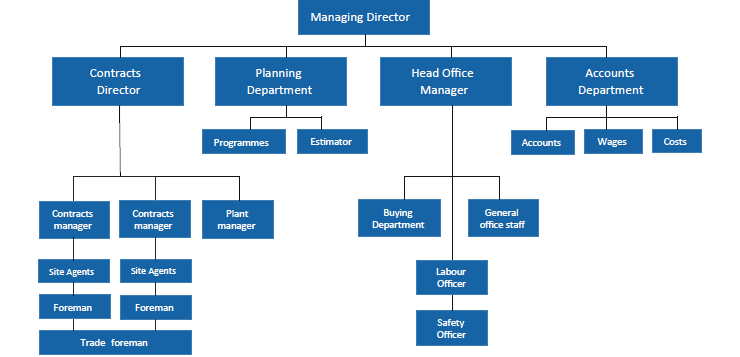

Building contractors can be categorised into the following groups:

- Emerging

- Small

- Medium

- Large

The Architectural Professional